What you need to know about the invasive zebra mussels taking hold across Western Colorado

Nearly impossible to eradicate, here's an explainer on their origin, what damage they cause and what you can do to help slow their spread

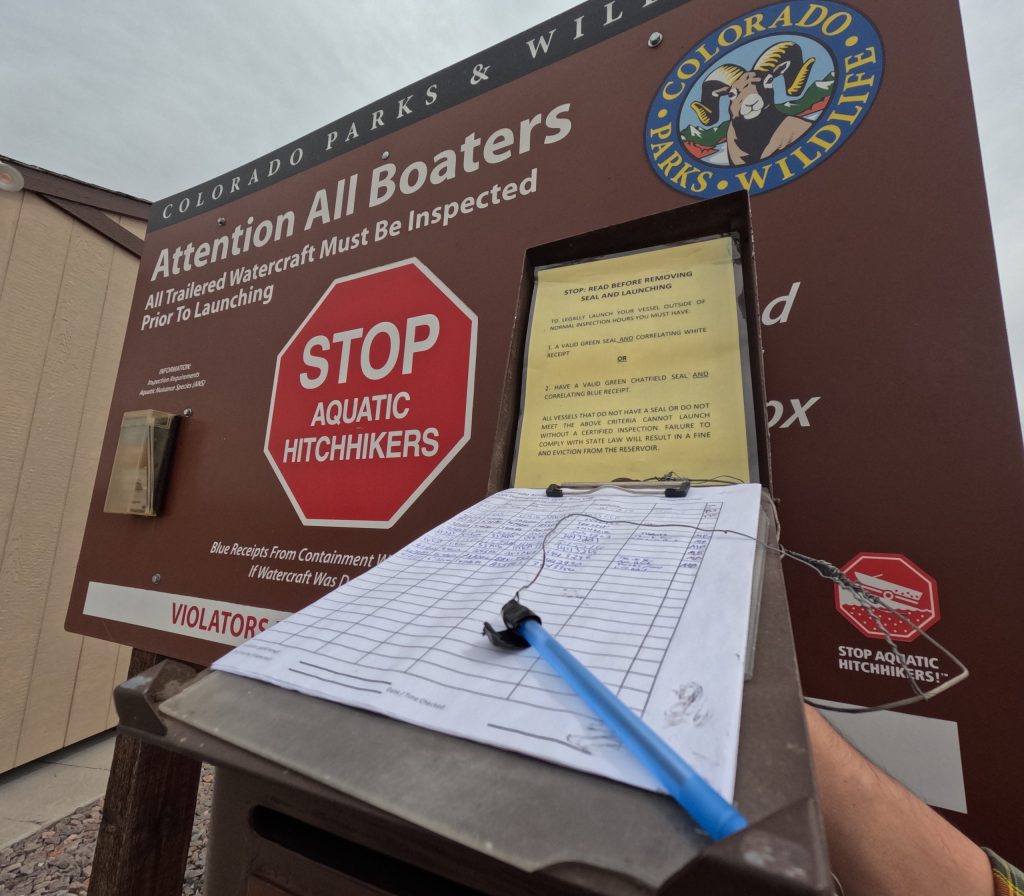

Colorado Parks and Wildlife/Courtesy Photo

Discoveries of the invasive and damaging zebra mussels have been piling up in Western Colorado, with recent detections in Eagle County, the Colorado River and other waterways.

Zebra mussels — and their microscopic, free-floating larvae called veligers — are notorious for their prolific reproduction and destruction of ecosystems and infrastructure. Once established, they’re nearly impossible to eradicate.

The species was first detected in the United States in 1988 in Lake St. Clair, which crosses the U.S.-Canadian border in Michigan. The species, which originates from Eurasia, spread rapidly across the Great Lakes and eventually made its way west. Today, the mussels continue to cause problems in waterways, impacting ecology, infrastructure and local economies.

Colorado’s first detection of an adult zebra mussel was in September 2022 at Highline Lake State Park outside of Grand Junction. Subsequent discoveries were made in the lake in 2023. By 2024, veligers were found in the Government Highline Canal — which feeds Highline Lake — and the Colorado River. This summer, in addition to more discoveries in the Colorado River and Highline Lake, Colorado Parks and Wildlife found veligers in Mack Mesa Lake in the state park and a significant number of adults in a private pond in western Eagle County.

What is a zebra mussel?

Zebra mussels get their name from the black and cream zigzag stripes on the shell. While in their larval stage, the mussels are invisible to the human eye; when adults, their triangular, D-shaped shell grows to about the size of a dime.

One thing that makes zebra mussels so destructive is that they are “extremely prolific reproducers,” said Robert Walters, invasive species program manager for Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

“A single zebra mussel can produce up to 30,000 offspring in a single spawning event and, under the right conditions, can spawn year-round with numbers going up as high as 1 million offspring from a single individual,” Walters said.

Like all mussels, they are filter-feeders, meaning they hang out at the bottom of a body of water and feed on things like algae, plankton.

However, the species itself has no natural predator in the United States, Walters said. While some fish may eat the mussels in small quantities, the consumption in no way matches their reproductive rate, he added.

Even humans are not really a likely predator for the zebra mussel. While they share in name with the saltwater edible delicacy found elsewhere and could technically be consumed, they probably shouldn’t be.

“Perhaps they’re edible, but you will probably burn more calories opening and getting the meat out than you can actually get from them,” said Rueben Keller, a professor at Loyola University in Chicago, specializing in invasive species. “The more serious concern is that they are filter feeders that live in pretty polluted environments and can build up quite high levels of pollutants that no person should be eating.”

Like other mussels, in their adult form, they can survive out of water for extended periods of time.

“In a moist environment with a more reasonable temperature, they’ve been shown to live out of the water for close to 30 days,” Walters said.

Without the shell, however, veligers do not last long out of the water.

How do zebra mussels spread?

In the majority of cases, human activity is responsible for transporting zebra mussels from one location to the next, Walters said.

“One of the primary vectors is recreational watercraft,” Walters said. “The mussels can actually grow on people’s boats if they are leaving their watercraft in the water for an extended period of time, and then if they don’t clean them off properly and move them from location to location, then they can move into the next body of water where people are going to recreate.”

Zebra mussels attach to structures with something called a “byssal thread,” which Walters described as a “root or anchor that they use to chemically and mechanically bond themselves to surfaces.”

In addition to boats, they can establish themselves on any recreational equipment that comes into contact with water: from fishing gear like waders to equipment like docks and barges.

As veligers float around in the water, if they drop and land on a hard surface — a rock, a dam wall, a boat, etc. — they will grow.

The “stunningly, large reproductive capacity,” allows them to spread “very, very quickly” and live at “very high densities,” Keller said.

Keller has studied the mussels’ spread in the Great Lakes and Midwest for over two decades, and said that many of the lakes no longer have sandy bottoms, but have what he described as “growing mats” of the zebra mussels.

In the Midwest, the mussels also likely spread from the Great Lakes into the Mississippi River, riding on board watercraft through a canal that runs through Chicago and connects Lake Michigan to the Illinois River, Keller said.

“Anywhere that you have these human-made channels that connect different water bodies, zebra mussels can move through those,” Keller said. “I think that’s really the biggest risk for the Colorado River system because there are so many channels that flow out of the Colorado River System and end up somewhere very far away.”

Reuben noted that researchers have had suspicions that the mussels could be spread on the feet or in the feathers of birds, but that it is extremely unlikely because veligers — which would be the only stage where the species could be moved like this —would not survive long out of the water.

While veligers can float downstream and cause spread through a river system, Walters said rivers do not have as ideal of a habitat as reservoirs or lakes for populations to establish and grow.

“I would anticipate that we might see larger or more extensive populations established in lakes and reservoirs than we would in rivers, but the rivers would allow them to move to other locations more readily,” he said. “The veliger is a soft-bodied organism, so the moving water is not great for their survivability. Whereas a lake or reservoir, the water’s not moving as fast. It tends to be more calm than a river system so it’s a more ideal habitat in which they can establish.”

What impact do zebra mussels have on water ecosystems and infrastructure?

As zebra mussels establish these dense populations and bond to surfaces, the impacts are significant.

However, one of the largest concerns is their impact on water infrastructure including irrigation systems.

“They very readily will grow inside of pipes and hydroelectric facilities and other infrastructure that needs to move water,” Walters said. “They can completely clog up pipes or mess with the way the hydroelectric facilities work, which can result in millions of dollars in damage.”

The Great Lakes have also seen how detrimental the mussels can be to the entire ecosystem.

“Anytime that you have a new organism — that gets to very high densities like the zebra mussels do — entering an ecosystem, it absolutely will have some serious impacts,” Keller said.

As a filter feeder that gets to these high densities, zebra mussels can outcompete and impact the entire food chain.

“We’re seeing in the Great Lakes that many levels of the food chain are suffering because zebra mussels are dominating all that energy that’s being produced at the bottom of a food chain,” Keller said. “In a non-zebra mussel system, the algae being produced gets eaten by small invertebrates, which get eaten by large invertebrates, which get eaten by little fish, which get eaten by big fish, but when all of that algae is just ending up in the zebra mussels, you lose all of those intermediate steps, and you also lose the bigger fish, which is something that we’re seeing in the Great Lakes.”

Losing these bigger fish could ultimately impact recreational opportunities offered and hit local economies that rely on the angling activity.

Rose Sandell, community engagement manager for the Eagle River Coalition, said that these impacts are of particular concern at a time when rivers and ecosystems are already strained.

“(Zebra mussels) concern us due to their potential for extensive, negative impacts on local ecosystems, infrastructure, recreation and the economy,” Sandell said. “With high river temperatures and low flows this summer, local ecosystems are already strained, so doing everything possible to protect these populations is vital.”

Why are zebra mussels nearly impossible to eradicate?

There have rarely been successful eradication attempts with zebra mussels and other invasive aquatic mussels, Walters said.

Some options include application of pesticides or molluscicide or the elimination of habitat in the form of draining the body of water where they’ve established a population, Walters said.

At Highline Lake, Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials have tried both methods to no avail. In addition to attempting to draw down the lake a dry and freeze out the mussels’ habitat, the agency tried several applications of a molluscicide in 2023.

The lake was drained in November, left dry through the winter and refilled in April. However, in June, Highline Lake — as well as Mack Mesa Lake in the state same state park — tested positive for zebra mussels. Parks and Wildlife does not know whether the mussels survived through the winter or whether they were brought into the lake from somewhere else, Walters said.

“There’s a lot of possibilities, so anything I would say is really just speculation,” Walters said, adding that generally, the mussels are “a pretty adaptable species and in a body of water; if you were to miss a couple of them, then that prolific reproduction thing kind of kicks back in.”

Part of the challenge in eliminating the species has to do with the nature of aquatic ecosystems, Keller said. With terrestrial animals and plants, there are options to selectively manage and tackle the problem.

“All of those options really are not available to us when we’re dealing with invasive species that live underwater,” Keller said. “Partly, they’re just so much more difficult to access and partly because it’s impossible in the water to selectively kill something.”

For example, a fish net could be cast, but every species of fish will be caught, not just one.

Keller said that in some small areas — like a hydroelectric power station — researchers have tried to disguise tiny pellets of salt, which is toxic to zebra mussels, as food for the invasive species. However, the application of a method like this is limited.

“The idea of applying that at the scale of the Colorado River or of the Great Lakes is just unimaginable,” Keller said.

“To date, nobody has come up with that sort of a silver bullet,” Keller said. “Once these things are well-established in a system, we just don’t have the technologies to reduce their impacts.”

How can you help prevent the spread of zebra mussels in Colorado?

It’s for this reason that the main “technology” to control their impact and spread lies in prevention work, Keller added.

Part of this also comes down to monitoring and detection.

“It is critical to understand where the mussels are so that we can implement additional measures to contain them or stop them from spreading into additional locations,” Walters said.

Parks and Wildlife has not identified a source for the recent discoveries in Western Colorado.

Walters noted that Parks and Wildlife surveyed 235 waters last year for the presence of not only zebra mussels, but any aquatic nuisance species in the state.

This year, it has continued to scale up these efforts, creating a dedicated monitoring team on the Western Slope and doubling the size of its aquatic nuisance laboratory in Denver to increase efficiency and the number of samples it can process.

As discoveries have continued in western Colorado, Parks and Wildlife has implemented a number of educational efforts to try and prevent their introduction in other watersheds, reservoirs and lakes. This is especially critical in areas where the species are not.

“If a species is well established, eradication becomes much more difficult and we focus our efforts on containment or limiting the potential for the species to spread into new locations,” Walters said.

The agency has launched an aquatic nuisance species program — urging users to “be a pain in the ANS” — which includes education efforts as well as multiple watercraft inspection and decontamination stations at reservoirs and stations for river users to clean and dry their gear.

“Anybody that’s out there recreating in any of our waters can help us stop this from getting any worse than it already is by cleaning and drying their equipment in between each and every use,” Walters said.

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

Readers around Steamboat and Routt County make the Steamboat Pilot & Today’s work possible. Your financial contribution supports our efforts to deliver quality, locally relevant journalism.

Now more than ever, your support is critical to help us keep our community informed about the evolving coronavirus pandemic and the impact it is having locally. Every contribution, however large or small, will make a difference.

Each donation will be used exclusively for the development and creation of increased news coverage.