Out of the Shadows, Part 1 | Crisis of care: What mental health looks like in Routt County

Darby McNamara was well-known in the community. He was an avid athlete, a talented artist and had an excellent sense of humor. It was his dream to go to culinary school and become a chef, having worked in the Steamboat Springs restaurant scene for a number of years. But on July 4, 2010, at age 21, he took his own life.

In school, he had been labeled a “problem child” and a behavioral issue. He became addicted to drugs and alcohol in middle school, and he was diagnosed with ADHD, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. There hadn’t really been talk of depression, which his older sister Meghan McNamara said seemed to exacerbate most of his issues, which she said started in childhood.

As a student, “I think (Darby) … kind of got pigeonholed a little bit into more of a disciplinary system rather than a supportive mental health treatment system,” Meghan said.

Meghan was 23 when her brother died by suicide. The two were born and raised in Steamboat, along with their younger sister Kaitlyn. Darby had been living in Huntington Beach, California, for about a year before his death. Being there was supposed to be a fresh start, but things weren’t working out. The last time Meghan spoke with her brother was the day he died when they shared details of how they planned to spend the Fourth of July. Her brother was planning to go to a nearby pier and watch fireworks with some friends.

“The last thing I said was, ‘Be safe and have fun,’” she said.

She believes if something could have been done before her brother started abusing drugs and alcohol, perhaps intensive therapy or medication, he might be alive today.

“I think some of the barriers that he faced with accessing mental health care are still very applicable,” she said.

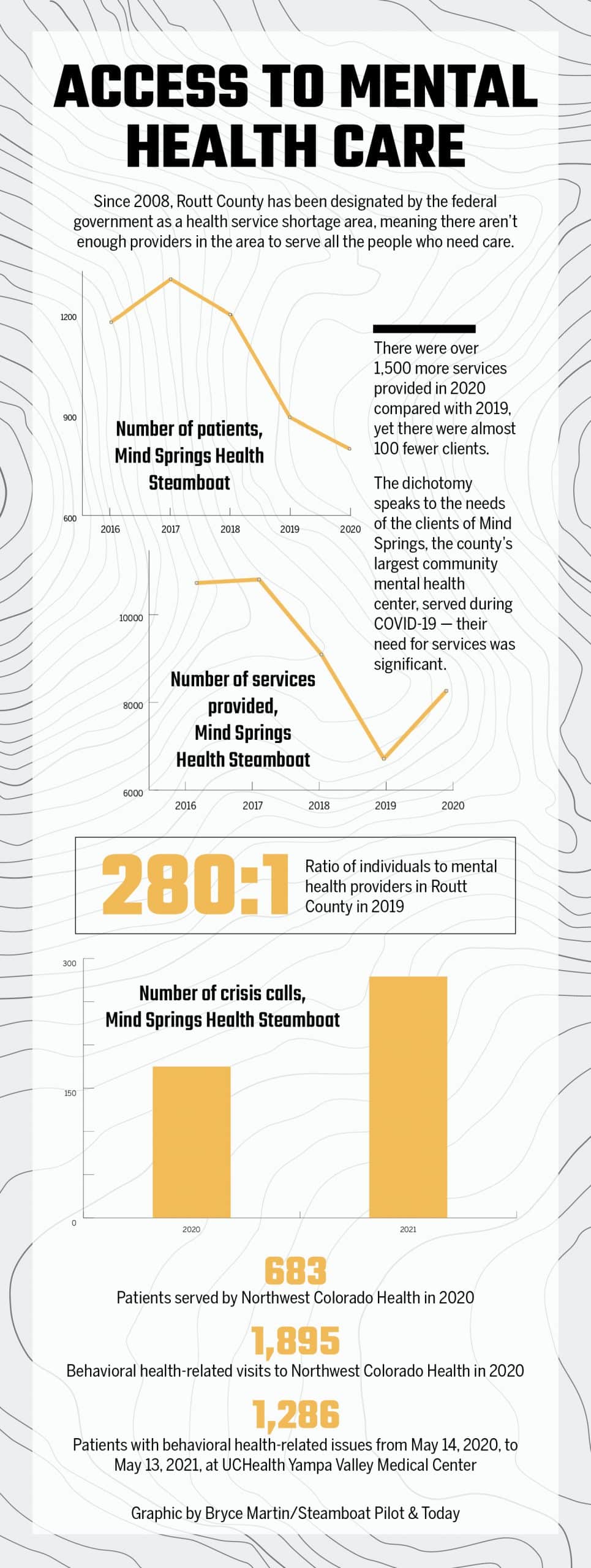

Those barriers begin with Routt County’s designation as a health service shortage area, a term used by the federal government, meaning there aren’t enough providers in the area to care for all the people who need care. Particularly through the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health stress points have been illuminated along with infrastructural weaknesses and other barriers to local care.

In 2020, Mind Springs Health, the county’s largest community mental health provider, saw 798 clients, delivered 8,201 services, such as therapy or counseling sessions, and responded to 175 crisis calls. Northwest Colorado Health, another community provider, served 683 patients in the past year and recorded 1,895 visits related to behavioral health.

UCHealth Yampa Valley Medical Center, which has its own crisis support team, identified 1,286 patients in the emergency department with behavioral health issues from May 14, 2020, to May 13, 2021. And those numbers don’t include the patients and services offered by the many private providers in the county, which aren’t affordable for everyone.

Gina Toothaker, outpatient program director for Mind Springs in Steamboat, said the stress from last year worsened an already struggling client base who were predominantly dealing with depression, anxiety and alcohol use. As the community’s safety net provider for the low-income, indigent and Medicaid population, Mind Springs sees clients with any and all mental health issues.

The increased service isn’t unique to Mind Springs, as Northwest Colorado Health and the hospital in Steamboat have seen the same.

“We have seen an increase in depression and anxiety and substance use, particularly alcohol, during the pandemic,” said Kelly Gallegos, chief nursing officer at the hospital and head of its crisis support team. “It’s real.”

The pandemic was also an opportunity for new behavioral issues to surface, which Toothaker attributed to the isolation and uncertainty of the time. Many people lost jobs, struggled with finances or endured the stress of suddenly having to homeschool their children, not to mention experiencing grief for sick or lost loved ones.

“I think that we saw a lot of the same sort of issues prior to COVID; it’s just bigger now,” said Toothaker, who added that Mind Springs is seeing people who have denied the reality of their issues but are now seeking help. “I think that’s why our client numbers went up so much after everything shut down.”

But mental health was already a concern well before the pandemic, so much so that in a 2019 Northwest Colorado Community Health Assessment, mental health was identified as the most pressing local topic needing to be addressed. The assessment, completed for Routt County and neighboring Moffat County, was a collaboration between UCHealth, Memorial Regional Health in Craig, Northwest Colorado Health and The Health Partnership. It was conducted through a combination of community surveys, provider subgroups and community forums.

The major issues identified included the inability to afford health insurance, addiction to drugs and alcohol, inability to afford mental health services and thoughts of or attempting suicide.

“It basically drives where are the needs in the community and how can we tailor to those,” Northwest Colorado Health Executive Director Stephanie Enfield explained of the assessment.

Dakotah McGinlay, left, hikes with friend Camille Hatch along Spring Creek in Steamboat Springs. McGinlay has lived with depression since childhood. (Photo by John F. Russell)

From parties to personal progress

Steamboat resident Dakotah McGinlay, who has lived with depression since an early age, said her struggles reached a peak during the pandemic.

She came to the area almost six years ago to study sustainability at Colorado Mountain College Steamboat Springs.

“I felt like this community was really welcoming, and there were components that felt very uplifting, like people taking care of one another or just sharing resources,” she said. “That’s what’s kept me (here) for a long time.”

Her story is similar to many people her age in Steamboat. She works seasonal jobs — and several of them — and is trying to find the right path in life.

She originally started seeing a therapist in college, but through working a season at Steamboat Resort, she was offered counseling through Mind Springs. She’s regularly seen a counselor there for the past two years and had her final appointment in early May. She will continue her therapy back at CMC.

McGinlay, originally from Colorado Springs, said her depression has taken different patterns over the years.

“When I was younger, it was very numbing; I didn’t feel anything, and that was scary because I’m a very emotional person,” she said. “When I didn’t feel anything, I didn’t know how to express my emotions.”

Now 25, McGinlay said her depression as an adult comes more in the form of existential crisis. She drowns in spiraling thoughts of what to do with her life and how to find more purpose, friends and security. That familiar sense of numbness returns, making it hard for her to get out of bed in the morning or meet anybody’s expectations, even her own.

“Once I start down that path, it’s like a downward spiral of self-worth and self-loathing,” she said.

She practices a more holistic approach to mental wellness. She’s never taken pharmaceuticals and instead relies on talk therapy, yoga and sobriety.

“I try to be as focused on self-growth and working through those funky feelings to the best of my abilities,” she said. “But I do need help every once in a while.”

As a college student in Steamboat, she initially enjoyed the party scene but has since focused on getting sober, which she said has allowed her to become acquainted with a much different group of people who are more mental health and wellness oriented.

“I have this new lens that says Routt County is particularly good at addressing these things … but there’s another realm to the mountain town that I think has a really hard time with mental health,” she said.

What Routt County does have

When people go without mental health care, it increases morbidity and mortality rates through suicide and overdose, according to Lilia Luna, behavioral health director at Northwest Colorado Health. Routt County has unique challenges regarding behavioral health care, being a rural area in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado with an escalating housing crisis and rising cost of living.

Certain populations in Routt County have more prevalent mental health issues, including elderly and youth, people who come to the mountains to distance themselves from others, veterans and the indigent. Issues also are more pronounced in marginalized groups, such as LGBTQ+ and people of color, which are at a higher risk for some mental health conditions because of a lack of support, safety or comfort.

For LGBTQ+ or Spanish-speaking populations, there are a lot of questions about safety, Luna said.

“Can I be accepted and treated with respect to being a transgender, or that ICE won’t take me or my kids? Fear acts as a big barrier for these populations.”

There were over 1,500 more services provided by Mind Springs in 2020 than in 2019, yet there were almost 100 fewer clients. The number of Mind Springs’ clients has steadily fallen over the past five years due to several factors, including decrease in staff, loss of the contract with UCHealth for in-hospital crisis response and loss of substance use disorder treatment groups. So far in 2021, however, Mind Springs has already nearly doubled last year’s number of crisis calls.

A shortage of mental health and substance use disorder providers has become a widespread issue plaguing the nation, particularly in rural areas. According to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, only 30% of the need for psychiatrists was met in Colorado in 2019, and nine counties — with a cumulative population of 2.6 million people — have no access to a psychiatrist.

In 2019, the ratio of individuals to mental health providers was 280:1 for Routt County, and 330:1 for the state overall. While better than the state’s ratio, it doesn’t take into account the expense of access.

“We need far more affordable providers in our area,” Luna said. “We do hit a lot of dead ends trying to get people that we see into specialty care, because there’s just not enough options.”

Locally, there is no specific medical detox facility, specialty treatment for eating disorders and very limited access to pediatric specialty care. There are no inpatient treatment centers that accept individuals who are uninsured, underinsured or unable to afford counseling or mental health services, whether that’s therapeutic or psychiatric. Neither is there an option for neuropsychological assessment, or “if there are, they come with a high price tag,” Luna said.

“Access in some regards is not that bad compared to some of the rumors I hear in the community,” Toothaker said, specifically referring to Mind Springs’ availability.

Mind Springs has been criticized by some for long delays when scheduling patient appointments, but Toothaker said that’s not true, as the center can typically get somebody in within a week to 10 days. Psychiatry, she explained, takes two to three weeks to get an appointment. Otherwise, Mind Springs, as one of two Medicaid providers in the county, is legally mandated to expedite appointments for those with Medicaid to no more than seven days.

Northwest Colorado Health also accepts Medicaid.

Lilia Luna is a licensed clinical psychologist and the director of behavioral health services at Northwest Colorado Health. She is the only bilingual mental health care provider in Routt County. (Photo by John F. Russell)

“Our services all complement each other; they’re not duplicative,” Enfield said. “We all exist on a different point on the continuum of behavioral health.”

Mind Springs, the largest mental health provider in the community, is part of a 10-county organization. It maintains eight full-time clinicians, five part-time clinicians, one full-time case manager and one part-time psychiatrist. Access to multiple psychiatric providers and other clinical staff throughout the Mind Springs service area is also available via telehealth.

Implementation of additional telehealth offerings early in the pandemic immediately ensured access to care and providers for UCHealth Yampa Valley Medical Center, as well as continuity of care for patients.

“Some patients were unable or uncomfortable coming to the hospital or clinic for an appointment, whereas for others, it was too risky for them to seek care in person,” said Lindsey Reznicek, communications specialist for Yampa Valley Medical Center.

The pandemic expedited the hospital’s existing plan to implement telehealth, which was originally going to take several years and instead took just two weeks.

Initially, there was some resistance and uncertainty as to the effectiveness of telehealth, according to Reznicek, “but once the pandemic forced the issue, it opened everyone’s eyes to the flexibility of telehealth along with its effectiveness.”

Perhaps Mind Springs’ most important service, according to Toothaker, is its crisis response. There are two full-time designated crisis clinicians who cover the majority of the 24/7 schedule and outpatient clinicians fill in the gaps.

While Steamboat’s hospital has no beds designated specifically for psychological needs, patients are treated and stabilized locally then connected to additional care elsewhere, either within the UCHealth system or not.

“We are able to provide our patients with almost immediate access to a social worker and evaluation, and a connection through either our virtual platform or others,” Gallegos said.

As part of the emergency department’s recent $10 million expansion, two unique safety rooms were added for patients in mental distress. That’s important as the hospital has been forced to sometimes serve as a social or medical detox environment.

Northwest Colorado Health offers integrated behavioral health services — which is when mental health providers visit with patients within a traditional medical office setting — at its federally qualified primary care centers in Steamboat and Craig. Integrated care is also available at its dental facilities in Oak Creek and Craig.

“We work hand-in-hand with our medical and dental provider teams to provide more of a holistic approach to health and wellbeing,” Luna said.

As a clinical psychologist, Luna or one of her staff will see patients during their medical or dental appointments as a strategy to decrease stigma surrounding mental health care. The good of this approach is to evaluate how a person’s overall health might be impacted by their emotional health, she said.

In addition to Luna, Northwest Colorado Health employs a psychiatric nurse practitioner, three licensed clinical social workers — two of whom have credentials in addiction counseling — and a licensed professional counselor.

“Northwest Colorado Health is a good net to catch people,” Luna said. “And if we’re not the right level of care, we’ll get other people involved who are the right level.”

In addition to being director of Northwest Colorado Health’s behavioral health program, Luna, to her knowledge, is the only bilingual psychologist or therapist in Routt County.

This photograph of the setting sun and her brother’s name written in the sand has special meaning for Meghan McNamara, who grew up in Steamboat Springs along with her brother Darby, who took his own life at age 21. (Photo by John F. Russell)

Lacking infrastructure for access

With no specific affordable, inpatient facility in Routt County to treat those with more severe mental health issues or substance abuse disorders, a group of concerned local citizens have been advocating to establish one here.

The primary inpatient facility used by Routt County patients is West Springs Hospital, owned and operated by Mind Springs Health and located about 200 miles away from Steamboat in Grand Junction. It’s primarily mental health focused, but there is a detox facility on its campus as well as a women’s recovery center.

The advocacy group would like to see a local facility encompass detox as well as inpatient mental health and crisis stabilization, which not all detox centers do.

Routt County residents Linda Delaney and Nancy Spillane are members of HARC, Healthcare Activists of Routt County, a 25-person group that includes medical personnel, elected officials and people who have worked on health care for the United Nations and around the world. The group was established in January 2017.

“As we have spoken with providers, people at the hospital, mental health care workers, people with Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp., law enforcement — it became quite clear to us that, not just in Routt County but in Northwest Colorado, mental health care needs are not being met,” Spillane said.

The primary reason, she said, is people can’t afford it. For instance, Spillane, a retired local educator and founder of Emerald Mountain School, had a relative who sought help at a residential mental health facility in Colorado, and his family had to come up with $30,000 to cover only nine days of care.

In a five-county area, which includes Routt, Rio Blanco, Moffat, Jackson and Grand counties, there is no formal detox space or psychiatric beds.

To help find a solution in bridging the gap, members of HARC made a presentation to the administration of UCHealth Yampa Valley Medical Center last fall.

“We started putting our energy, about two years ago, into interviewing as many people as we could in these five counties — providers, school counselors, law enforcement — and we have not found one person or one organization that disagrees with us,” Spillane said. “Everybody agrees — we need detox; we need psychiatric beds.

“We want to see something done because too many of our friends and neighbors are dying, and family members,” Spillane said. “We want them to get help here, where their loved ones are.”

Darby McNamara was one of Spillane’s students when she taught in Steamboat.

“(His family) tried different ways to help him through a severe depression,” Spillane said. “They tried using their church — all of the intentions were good and certainly honorable, but not the professional help that this child needed. He made it to age 21.”

Darby started using drugs and alcohol in late middle school and early high school, according to his sister Meghan, who still resides in Steamboat.

“Like so many people he was self-medicating, trying to find relief from what he was experiencing emotionally,” she said.

He, ultimately, went to a treatment facility for people with both substance abuse and mental health issues in Glenwood Springs while still in high school. At that point, Meghan recalled her parents had to sign away their legal rights to Darby, who was still a minor, to get him the treatment he needed.

Despite efforts to create a local mental health facility, the data doesn’t suggest an overwhelming need in Routt County, according to Soniya Fidler, president of UCHealth Yampa Valley Medical Center.

“Anecdotally, without that data support, I’m not seeing a need for a certain number of beds, because it is still a small number of those who need inpatient psych facilities,” she said. “I’m seeing a lot more need from an outpatient standpoint.”

In 2019, the hospital transferred 45 people from its emergency department to an inpatient treatment facility in Colorado. That number increased to 67 in 2020. Mind Springs had 32 in 2020.

“That’s not even one patient a day,” Fidler explained. “We do need a certain average daily census to put up that type of service and do it well and keep staff competent in doing that well.”

For example, the hospital’s average daily census for inpatient medical care is usually around 10 and can fluctuate anywhere from two to 21.

“An inpatient psych facility is something we’ll continue to assess and evaluate. We want to see the data to support it — what is the need; can we sustain that level of service?” Fidler said.

Misunderstandings about mental health

While access is typically at the top of the list of mental health barriers, other factors have also been identified, such as Routt County’s persistent “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality and an overall misunderstanding of mental health.

“It’s real, and it’s treatable,” Toothaker said of mental health issues. “They are physically based just like any other illnesses that people deal with.”

There is physical evidence of anxiety seen under the microscope and in a person’s mobility, Luna said.

“Emotional health is physical health and vice versa,” she said. “The more we can integrate that concept and treat people as whole individuals, the better off people will be.

“Bootstrap mentality on its own leaves people susceptible to more suffering and pain,” Luna added. “There’s going to be risks and benefits to any strategy you take. The hope is that people are able to choose the strategy that promotes their health.”

And mental health is certainly a process, as McGinlay has found.

“Those who are within the mental health realm, they’re working towards it,” she said. “It’s not like they cross a bridge, and they have mental clarity, and they feel amazing every day. No matter who you are, we’re all human; we all suffer. Just to know there are services out there that help in reducing that suffering, I think, is empowering to say the least.”

The hope is that one day seeking help for mental health or engaging in prevention techniques, such as regular therapy, is applauded and not judged, Fidler said.

“When my kids were asked what they were doing last summer, they would say they do mountain biking and football and therapy,” she said. “That’s where we want to get to. We want it to be something that just comes out of their mouth.”

The newly renovated emergency department at UCHealth Yampa Valley Medical Center included two private behavioral health “safe rooms,” upgraded to provide more advanced care in a secure environment particularly a protective door that can be closed to create a safe environment for patients. (Photo by John F. Russell)

Working on the cause

Processing past traumas has been important to McGinlay’s therapy. She’s been able to reflect on situations in her life, with the help of a licensed professional, and now mental health has become part of her journey of self-care and self-love.

“It was a safe place to talk about whatever I needed to talk about,” she said.

She found talking to a trained counselor was preferable to talking with friends or family who always wanted to voice their opinions.

“To be in the therapy environment is where I can be level-headed and really try to figure out what’s best for me and how to be the best version of myself,” she said.

When she would walk into the Mind Springs office or get on a phone call, she felt like she was doing something good for herself, “even though sometimes it’s really hard, I know that it’s worth it.”

While McGinlay was willing and able to find help, not everyone is. Challenges with mental health care are being identified, and there are several ideas already gaining ground in Routt County.

“When you look at it from a broader lens, what we really need to do is attack it from the other side and provide more preventative services, destigmatize it, make sure we have behavioral health implanted in all of our clinics and really work on those transitions of care and handoffs,” Gallegos said.

Yampa Valley Medical Center is seeing a need for prevention and early identification of mental health issues, according to Fidler. One of the ways to expand access, which was cemented through the pandemic, is through virtual care.

There also needs to be a focus on outpatient programs for substance use, as well as detox, which the hospital does to a small degree from a medical standpoint. There’s a greater need for social detox when patients don’t necessarily need medical care but need a safe place to detox after a long night, Fidler said.

“With Routt County being one of the healthiest counties in the nation from a physical standpoint, we should be thinking the same way from the emotional standpoint,” Fidler said.

Perhaps one of the largest examples of expanding mental health service is UCHealth’s pledge to contribute $100 million toward care in Colorado, including in Routt County. The first phase of that has been integrating behavioral care into primary care settings. Integrated behavioral care is available at Yampa Valley Medical Center’s obstetrics clinic in Steamboat and primary clinic in Craig.

“When we embed our behavioral health professionals within a primary care team, it expands the services,” Fidler said.

And when behavioral health is integrated into traditional medical visits, appointment show rates increase, she said.

Northwest Colorado Health pioneered integrated care locally in 2015. It seemed like a simple idea. A person could go to a medical health appointment and be screened for behavioral health and have a professional come into the room all in one visit.

“Community health centers in general across the country were the forerunners for that model,” Enfield said.

In November, UCHealth added an outpatient behavioral health clinic in Steamboat, staffed by Amy Goodwin, a licensed behavioral counselor and Level 3 certified addictions counselor.

Northwest Colorado Health also has plans to expand its services, particularly for some local populations that go underserved.

However, the barrier to expansion is finding qualified licensed practitioners, even as the facility’s revenue model allows for expansion.

To deal with local crises, Mind Springs has started a new law enforcement co-responder program with the Steamboat Springs Police Department. Prior to the program’s inception, local law enforcement would respond to a call and then determine if a person needed mental health support. At that point, they would transport the person either to the Mind Springs office or to the hospital.

“This is really just taking out the middle step where we’re not sitting around waiting for law enforcement to give us a call if they need us,” Toothaker said.

Through the new program, mental health professionals are on scene when a situation involves behavioral health issues.

Based on the success of the program so far, Toothaker envisions expanding the program into the Routt County Sheriff’s Office and EMS.

UCHealth, with funding support from the Craig Sheckman Family Foundation, has also implemented behavioral health services in all Routt County’s school districts. They then contract with Mind Springs for clinicians to be based at the schools.

“They work with kids, a little bit with families, they coordinate a lot with school staff and they can refer them back into our clinic if they need psychiatry or some other service,” Toothaker said. “In schools — that’s where mental health really starts.”

To reach Bryce Martin, call 970-871-4206 or email bmartin@SteamboatPilot.com.

Mental health resources in Routt County

Mental health resources in Routt County